Deep time (using Tensorflow to read clocks)

09 Oct 2016This is a simple project with the aim of learning to tell time from an image of a clock like this one:

The code is available here: https://github.com/felixduvallet/deep-time-reading

In a nutshell, the approach looks something like this:

- Generate a synthetic clock face with different times shown (input data).

- Use tensorflow batch queues to provide a parallelizable input pipeline.

- Formulate this problem as a multi-task classification problem, where one task is to predict the hour and one task is to predict the minute.

- Use (essentially) CIFAR10’s model architecture.

- Optimize cross entropy loss

- Also measure prediction precision and time error (how far off our time telling is from the truth).

Disclaimer: This is a side-project I decided to start to learn a bit more about Tensorflow’s architecture and data flow pipeline. This is not meant to be a production-level solution, it is sandbox where we can quickly evaluate many models and experiment with different features of tensorflow. To get fast model learning, I decided to use very ‘easy’ images of clocks (i.e. synthetically generated ones that look the same). As such, it’s clear that deep learning is overkill for this particular problem, but this implementation still provides a nice demonstration of tensorflow’s neat features.

Contributions are welcome via issues and pull requests. If this code is helpful to you, please star the repository.

This post is pretty long, so essentially we will discuss:

- Generate clocks

- Setting up a data input pipeline

- Defining a multi-task deep learning classifier

- Optimizing the model using tensorflow

- A few loss functions we can use

- Evaluating the trained model

- Looking at the probability distribution for one image

Generating clocks

While it would be awesome to go out and get a bunch of pictures of clocks and label them with their time, that would make a sizeable project in its own right (probably involving existing image databases, some cropping, and Amazon Mechanical Turk).

Instead, I decided to use synthetic images of clock faces, because images are easy to generate and by definition are annotated with the correct time.

The code for generating arbitrary clocks is in generate_clocks.py, and uses matplotlib.

Currently only hours and minutes and drawn, but seconds are supported if you want to make the problem more complicated.

The script generates 57x57 images of clock faces with a time, for example:

Why this size? Well, larger images would take longer to train, and this was on the small end of image sizes resulting in a “good looking” clock.

So let’s generate a bunch of clocks!

NOTE: Instructions for running code are shown in quotes like this:

Run the code to generate a bunch of clocks:

python clock_reading/generate_clocks.py

It will create a directory full of clock images, and also an index file (clocks_all.txt), which lists the filename and ground truth time (hour and minute) for all generated clocks.

Since we generate a clock for every single minute over 12 hours, we get 720 clock images and 720 lines.

We can now separate the 720 examples into independent train & test sets using the shuf utility (in OSX, install coreutils and use gshuf).

Let’s take 80% of the data as training examples (576 images) and the rest as test set:

shuf clocks_all.txt > clocks_rand.txt

head -n 576 clocks_rand.txt > clocks_train.txt

tail -n 144 clocks_rand.txt > clocks_test.txt

Now we have data (clock images) and an index file that provides the ground truth label (hours and minutes). We are ready to start learning.

Deep learning using Tensorflow

We will treat this problem as a classification problem on both hours and minutes. More concretely, the classifier will take an image and predict two integers, one from 0 to 11 for hours, and another from 0 to 59 for minutes.

Tensorflow input pipeline

Our input index file has filenames, hours, and minutes (tab separated) and looks something like this:

clocks/clock-09.12.00.png 9 12

clocks/clock-07.53.00.png 7 53

clocks/clock-11.20.00.png 11 20

clocks/clock-03.51.00.png 3 51

We now need to load the images into a format Tensorflow can understand (i.e. Tensors), and get ground truth labels (hours and minutes). For this we will use tensorflow Example Queues, which are well explained in the documentation.

The code in clock_data.py reads the contents of the index file (such as the one above), then creates a string_input_producer which is a queue where elements are lines from the index file.

The most important work happens in read_image_and_label, where we do the following:

- Separate a single line into the filename, hour, and minute.

- Read the contents of the file into a Tensor.

- Decode the image, (optionally) convert it to a grayscale (

channels=1), and cast to a float. - Set the image Tensor shape (for some reason

decode_pngdoesn’t do this). - Normalize each image (zero mean, unit standard deviation).

- Convert the hour and minute strings into integer Tensors.

Then, we use tf.train.shuffle_batch to create batches of examples (by default, 128 examples per batch) with a random ordering.

An important point is that the string_input_producer queue cycles through the input, so we never run out of examples during training (or evaluation, for that matter).

Tensorflow model for multi-task prediction

For our computational model layout we will use basically the CIFAR10 model of Alex Krizhevsky available in the tensorflow codebase.

First, a historical aside you can easily skip:

I first made sure the CIFAR10 model is acceptable for this task at all (i.e. it can make sensible classifications) by first building a model that predicted a single class (hours or minutes) from a clock image. The performance on this problem was scarily good, and the model trained very very quickly.

For code simplicity & sanity I decided not to keep this single task model, as it was going to be a pain to maintain every piece of code twice (once for predicting one output and once for a predicting two outputs). If you want to run this base model yourself, you can remove one of the two softmax outputs from the model & loss function.

The classifier will take as input a clock image and predict the time (hours and minutes). At the output, the final layer will be a fully-connected linear softmax layer (i.e. multi-class logistic regression) that produces a probability score. In the middle, we will use the CIFAR10 model. Since the CIFAR10 model is very well explained elsewhere, here we will focus on the multi-task prediction aspect of this model.

In this problem of reading time from clock images, the classifier will be tasked with predicting two classes: a 12-dimensional distribution (for hours) and a 60-dimensional distribution (for minutes). While we could theoretically train a model for hours and a model for minutes, this would be a lot of duplicated work. However, if you think about it a lot of the problem structure (isolating clock hands, finding their location, etc.) is shared across both problems.

We will thus leverage the concept of multi-task learning, where one computation graph is tasked with predicting two different outputs using (almost) entirely the same structure. All the layers are shared, except for the output layer which is duplicated: once for hours and once for minutes In this way, the model uses the same parameters for all shared layers.

The loss function (what tensorflow will attempt to minimize during learning) will be two cross-entropy terms (one for minutes and one for hours) added together. The individual loss function looks like:

def loss(logits, labels):

cross_entropy = \

tf.nn.sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(

logits, labels,

name='cross_entropy_per_example')

cross_entropy_mean = tf.reduce_mean(

cross_entropy, name='cross_entropy')

And we combine two of them to end up with a cumulative classification loss:

loss_hours = loss(logits_h, labels_h)

loss_minutes = loss(logits_m, labels_m)

tf.add_n([loss_hours, loss_minutes], name='loss')

Note that this is the loss that gets optimized during training. The file clock_model.py specifies the inference graph, the loss function, and the training operation (the optimization procedure).

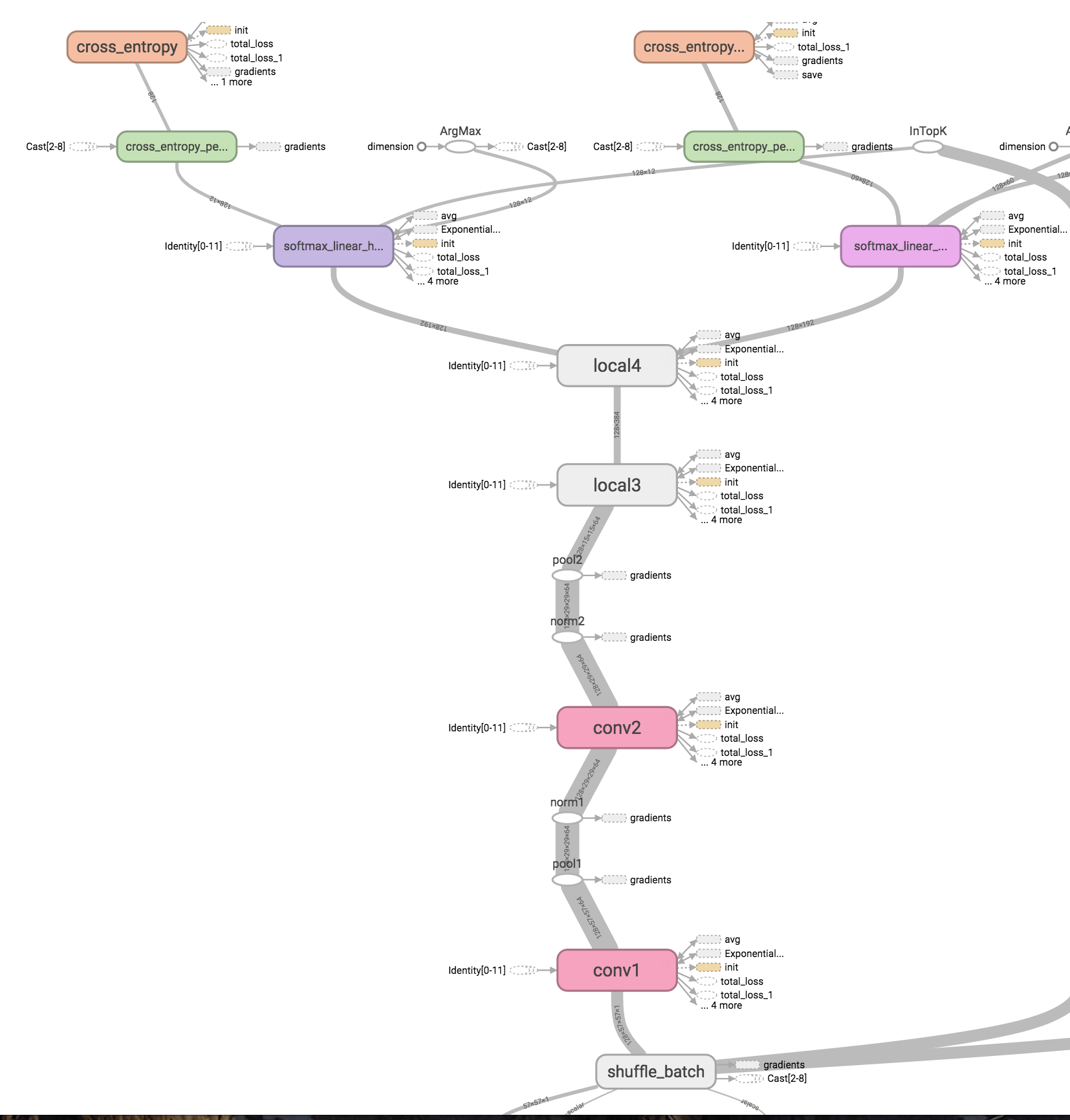

In Tensorflow, the final model looks something like this:

As you can see, the input image queue (shuffle_batch at the bottom) is fed through several layers of the graph. After the ‘local4’ layer, the pipeline splits into two outputs: one softmax classifier for hours and one for minutes. We also have two cross entropy loss functions.

Learn!

(NOTE: We’ll now run the tensorflow code, so make sure you have tensorflow installed.)

The file clock_training.py instantiates the model defined above, loads the data queues, and handles a lot of book-keeping during training.

Start running the training pipeline:

python clock_reading/clock_training.py

This will load all the images (and labels) into a never-ending data pipeline (by repeating the input), shuffle the order of the data, and train the model.

Every few iterations you will see the loss (cross entropy) for the current step, as well as the prediction and time accuracies (on the training data). We also save the latest model periodically, to later load it and evaluate the performance on held-out data.

Visualize the loss over time using tensorboard:

tensorboard --logdir tf_data/ --reload_interval 15

And navigate to http://localhost:6006/ to see the learning progress.

NOTE: We store all runs of tensorflow as separate sub-directories inside tf_data/, these will all show up in tensorboard as different runs (with a different color).

Simply remove the tf_data directory and restart tensorboard to clear these out.

Evaluating the learned model

In addition to the cross entropy loss optimized during training, we are interested in other loss functions that will help us evaluate the performance of our system. These are defined in clock_model.py and clock_training.py.

-

Classification precision

One useful metric is to know how often we get the classification correct (i.e. the classifiers predicts

minutes = 15and it matches ground truth).We use tf’s

in_top_kwith k=1 to do exactly that, for both hours and minutes.train_accuracy_h_op = tf.nn.in_top_k( logits_hours, labels_hours, 1) train_accuracy_m_op = tf.nn.in_top_k( logits_minutes, labels_minutes, 1)This is shown in the log as follows:

training set precision = 0.169(h) 0.034(m) (640 samples)means we got 16.9% of the hours correct and 3.4% of the minutes correct. Note this does not account for how far off any prediction might be, being wrong by one minute is the same as being wrong by 29 minutes. We average the two precisions to get a combined precision measure.

-

Time error

We can also compute a loss which measures how far off our predicted time is from the true time. We will compute this difference (expressed in minutes) in

clock_model.time_error_loss(-):avg_error_c = tf.reduce_mean( wrap(tf.sub( tf.add(60 * hours_predicted, minutes_predicted), tf.add(60 * hours_true, minutes_true)))where

wrap(-)just ensures we wrap around the clock when computing time differences, so that the time difference between 9’58 and 10’02 is always 4 minutes. We’ll compute this loss for full time (hours and minutes combined), as well as just hours or just minutes.Side note: Tensorflow’s

modoperator works differently than python’s, so we have to do some more work to ensure we get the correct wraparound time difference operator.

During training, the optimization loss (cross entropy), the classification precision, and the time error are all computed over the training data. These are also summarized in tensorboard as loss, training_precision, and training_error respectively.

Running the evaluation pipeline

In clock_evaluation.py, we have a separate evaluation pipeline. This enables us to compute the validation set accuracy during the training optimization, and see how well we are doing on a held-out set of clock images without stopping the training procedure.

The evaluation procedure looks like:

- Instantiate the model (same as the training)

- Set up a data pipeline on held-out validation (or test) data

- Then, every few seconds:

- Load the latest trained model file (sets the parameters)

- Run the model on the held out data

- Report metrics

Let’s run this at the same time as the training pipeline.

Run the evaluation pipeline

python clock_reading/clock_evaluation.py

This will report the holdout accuracy every few seconds (a few = 30 by default).

NOTE: When multiple runs are available in tf_data/, the evaluation loads the latest one (ordered alphabetically).

Visualize in tensorboard:

tensorboard --port 6007 --logdir tf_eval/ --reload_interval 15

And navigate to http://localhost:6007/

Reading time from a single clock

It’s also possible to read a single clock image and look at the actual distribution of predicted times predicted.

For this, we first have to convert the output of the model (log-likelihoods) into actual softmax probabilities:

(logits_hours, logits_minutes) = clock_model.inference_multitask(image)

likelihood_h = tf.nn.softmax(logits_hours)

likelihood_m = tf.nn.softmax(logits_minutes)

When we run these, the output will be an actual probability distribution over labels. We can then sort these in descending order to look at the most likely classes (for hours and minutes).

Run the clock prediction on a single hour & minute pair.

python clock_reading/read_single_clock.py --hour 1 --minute 5

This will load the clock image for 1h5m, build the same computation graph as before, load the parameters from the latest model, and run the predictor on the image. (Note: you can also specify the image file directly if you want to load a file not in the original set.)

Here, this example is predicted correct (the true time is 1h5m, and it predicts 1h5m), for instance in this run:

==================

Top 3 predictions:

H 1 (p = 1.00) * | M 5 (p = 0.99) *

H 0 (p = 0.00) | M 4 (p = 0.01)

H 2 (p = 0.00) | M 6 (p = 0.01)

==================

Truth: H 1 | M 5

We show the top three predictions (for hours and minutes) in decreasing order of probability. The star shows the true class. The hour predictor is very confident about its prediction, the minute is just slightly less so (note that numbers don’t add to 1.0 because of rounding in the printing).

This example is off by 60 minutes, predicting 6h59m instead of 5h59m.

==================

Top 3 predictions:

H 6 (p = 0.54) | M 59 (p = 0.91) *

H 5 (p = 0.46) * | M 58 (p = 0.07)

H 11 (p = 0.00) | M 0 (p = 0.02)

==================

Truth: H 5 | M 59

As you can see, while the minute prediction is quite certain (.91 vs .07), the hour prediction is quite ambiguous (.54 vs .46), with the higher-probability class (6) being wrong.

Keep in mind this is running on my trained model; your results will most likely vary.

Observations & Notes

Performance is usually quite good here since it’s a very simple problem: the data is very clean and highly structured. However, sometimes the model fails to converge to a good solution, even on the training data. This is usually worse for the minutes prediction. When this occurs, just restart the learning. By step 300 (or so), your trained model should have very low error on the training data.

The model usually gets 100% precision on the training data (again, this is a very simple with very structured data so we expect quite good performance). The test precision is not quite as high, but looking at individual samples shows that when the model makes a mistake, it can often be just off by a single minute, as for example:

Predicted 10'12 -- Actual 10'11 Error: 1.00

Predicted 00'02 -- Actual 00'03 Error: 1.00

Predicted 07'29 -- Actual 07'30 Error: 1.00

Predicted 06'25 -- Actual 06'24 Error: 1.00

Predicted 03'42 -- Actual 03'41 Error: 1.00

Not bad!

Future Work

Here are some suggestions for future work:

- Train a regression model instead of classification.

- Use an embedding projection to learn a lower-dimensional embedding of the clock images.

- Generate different clock faces.

If any of these appeal to you, feel free to fork this repo and submit a Pull Request.